Emergency Relief Coordinator Mark Lowcock was briefing ambassadors on the Secretary-General’s recommendations for keeping more civilians safe from harm, noting that despite the UN chief’s call for a global ceasefire during the COVID-19 pandemic, deadly fighting had continued, and worsened in some areas.

Last year, conflicts contributed to a rise in those forcibly displaced, to 80 million by the middle of 2020. Those able to return home also decreased, while insecurity, sanctions, counter-terrorism measures and red tape, “hindered humanitarian operations.”

The pandemic made it harder with flight suspensions, borders closed, quarantine measures and lockdowns. Mr. Lowcock highlighted five key areas where improvements are most needed.

Conflict and hunger

The interplay between conflict and hunger saw the threat of famine emerge again, in northeast Nigeria, parts of the Sahel, South Sudan and Yemen, said Mr. Lowcock, creating a year-on-year increase of 77 million people facing “crisis or worse levels of acute food insecurity as a result of conflict.”

In Nigeria, 110 farmers died in a single attack on a rice farm. In Ethiopia, crops have been destroyed and looted, while relief was blocked following the political crisis in Tigray. The relief chief said he had written to ambassadors earlier in the day about what needs to be done there.

He called for “more effective action” by governments to address the problem overall, noting that conflicts disrupt food systems and markets, while food is destroyed and prices rise – a vicious cycle of hunger.

Urban warfare

Second, he noted 90 per cent of people killed by explosive weapons, live in cities and towns, compared to just 20 per cent when they’re deployed in the countryside.

“These weapons also inflict a devastating toll on essential civilian infrastructure”, said the relief chief. “Fighting parties must change their choice of weapons and tactics.

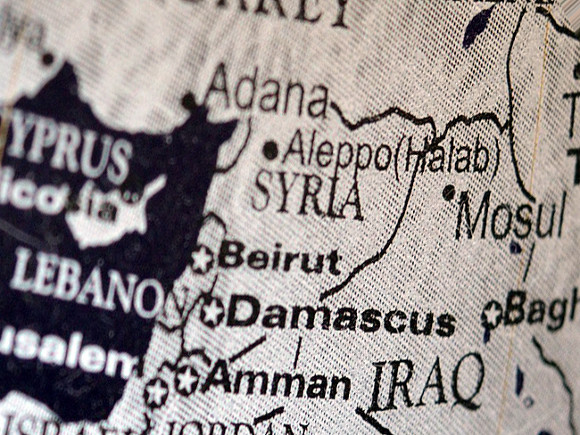

He also highlighted the impact of conflict on the environment, citing airstrikes in Iraq which destroyed field through wildfires, threatening biodiversity and endangered species. Oil spills in Syria had polluted farm water, endangering health and hygiene.

“The origin of many of many conflicts is found partly in environmental issues, especially those related to water”, he said, predicting that Council business would see many more consequences of this, in the years ahead.

Medics under fire

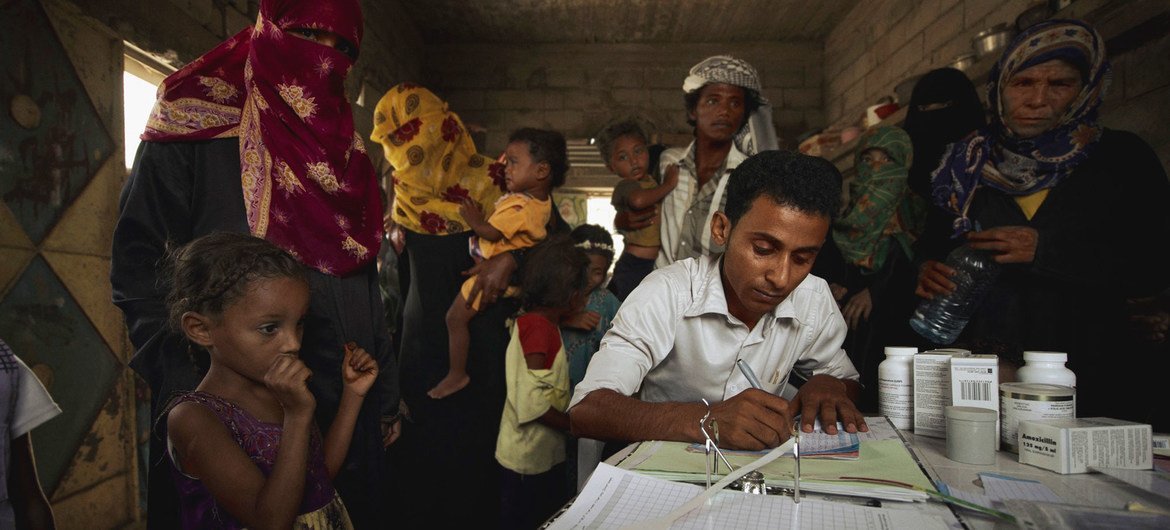

“When medical care stops, lives are lost” said Mr. Lowcock, bluntly assessing the impact of how attacks on healthcare personnel and facilities caused yet more death, on top of conflict.

Attacks on healthcare across 22 conflict-affected countries killed 182 health workers last year, and in Myanmar alone, following the military coup, 109 incidents of violence against staff were documented in a two-month period “accelerating the collapse in the public healthcare system when many people have needed it most”, he said.

“The consequences on healthcare are catastrophic, depriving millions of people of lifesaving care, and severely reducing the treatment of diseases like cholera, measles and COVID”, he added.

Some States have taken practical steps to protect medical staff, most importantly by ensuring military rules of engagement respect international humanitarian law.

Changing behaviour

Finally, Mr. Lowcock warned ambassadors that in his four years on the job, he had seen a “significant deterioration” in compliance with humanitarian law, on the part of belligerents.

“It is possible to make progress” he said, calling for States to improve training, modernise policies to avoid civilian harm, adopt better tracking of casualties, investigate incidents, and hold those guilty of violations to account.

He added that the behaviour of non-State armed groups to comply with international law could also improve, “though it is important to recognize the very real challenges in this area, especially in respect of those groups who refute international humanitarian law and the role of humanitarian agencies, as part of their twisted ideologies.”

“We all – Member States and humanitarian agencies in particular – need a more effective approach to tackling this. Many current efforts are counter-productive and exacerbate harm to civilians.

What is not punished, is encouraged’

Accountability is crucial, he concluded, telling the Council that “if war crimes go unpunished, things will get worse. Accountability for violations must be systematic and universal. What is not punished, is encouraged.

“This takes political will…to investigate and prosecute allegations of serious violations whenever they occur. We have the laws and the tools to protect civilians from harm in armed conflicts. It is time that all States and parties to conflicts, apply them.”